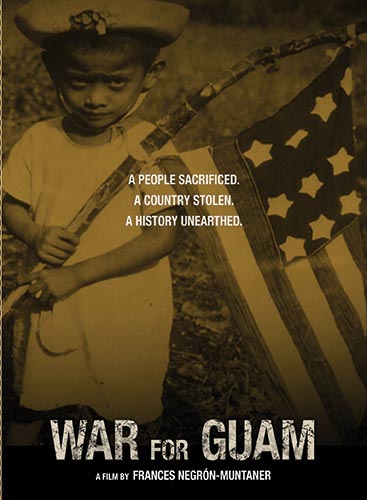

War for Guam

WAR FOR GUAM is a 57-minute film about World War II and its enduring legacy in Guam, a U.S. territory since 1898. The film tells the extraordinary story of how the Native people of Guam, the Chamorros, remained loyal to the US under a brutal Japanese occupation. Through rare archival footage, contemporary veritè, creative use of graphics and sound as well as testimonies of survivors and their descendants, the program is told from various points of view. These include war survivors like Antonio Artero, Jr., whose father was awarded one of the first Medals of Freedom for his heroic deeds when protecting American lives; and two key historical figures, Radioman George Tweed and Father Jesus Baza Duenas.

When the war began in Guam on December 7, 1941, Father Duenas was a thirty-year old Chamorro priest who immediately decided to stand up for Chamorros by openly defying the Japanese authorities attempts to change their religious beliefs, cultural traditions, and political loyalty to the United States. George Tweed was a 39-year-old American Radioman who had decided to flee into the jungle rather than be sent to a prisoner of war camp in Japan. Although unarmed and under constant surveillance for any signs of disaffection, the Chamorros decided to protect Tweed, often facing torture and death so that he could avoid capture. The stories of Chamorro families, George Tweed and Father Duenas dramatically intertwined when after nearly three years of occupation, Father Duenas, alongside two other Chamorro men, were executed for refusing to give information on the soldier’s whereabouts. Hours later, the US military rescued Tweed before beginning the takeover of Guam.

The Chamorros, who had been interned in a concentration camp with some having witnessed a series of massacres, welcome the US soldiers as saviors from death. Yet, immediately after Guam’s liberation on July 21, 1944, the US proceeded to confiscate three quarters of Guam’s land mass for military and recreational purposes. Chamorros responded with a drive for the people of Guam to become US citizens, believing that such status would protect them from the land takings. Six years later, Chamorros became US citizens but there was no significant devolution of land. Instead, Guam was quickly ushered into a market economy where most activity revolved around military contracts and military service.

Marginally employed or working for the military, Chamorros initially found it difficult to seek justice. But as Chamorros increasingly felt like squatters on their own land, the memory of the war started to change from that of being rescued to that of being reoccupied. Thus, a new struggle began.